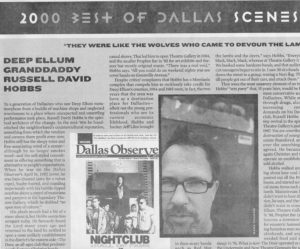

Deep Ellum granddaddy Russell David Hobbs

By Jimmy Fowler

To a generation of Dallasites who saw Deep Ellum metamorphose from a huddle of machine shops and neglected warehouses to a place where unexpected and unsettling performance took place, Russell David Hobbs is the spiritual architect of the change. In the mid-’80s he hand-stitched the neighborhood’s counter cultural reputation, something from which the vendors and owners there profit even now. Hobbs still has the sleepy voice and free-associating mind of a stoner — although he no longer smokes weed — and the self-styled commitment to offering something that is alternative to people’s expectations. When he was on the Dallas Observer’s April 16, 1987, cover, he was bare-chested (save for a velvet cape), bushy-haired, and standing imperiously with his bubble-lipped overbite above a crowd of musicians and partiers at the legendary Theatre Gallery, which he dubbed “an open sore of culture.”

His plush mouth had a bit of a sneer about it, but Hobbs seems less arrogant today. He famously found the Lord many years ago and returned to the land he settled to open a most unlikely establishment in the district’s far eastern side — The Door, an all-ages club that predominantly features Christian bands.

“I have never been very interested in making a lot of money,” Hobbs says. “I used to call what I earned ‘psychic income.’ I’ve always wanted to provide a place where someone can stand up on the stage and play a song that he wrote. That’s a very beautiful thing.”

But back to the heathen times, when a mid-20s Hobbs tried to make sense of the world. “I was in traditional society and trying to find my place in it,” says Hobbs, a Richardson native who studied design, business, architecture, and biology in college while on his way “to find the truth; that’s what we all want.” He was living in a warehouse on Greenville Avenue that was big enough to accommodate his friends and their bands; he provided the keg and the smoke, and gradually more and more people came to these still very casual shows. That led him to open Theatre Gallery in 1984, and the smaller Prophet Bar in ’85 for art exhibits and theater but mostly original music. “There was a real void,” Hobbs says. “All you could do on weekend nights was see cover bands on Greenville Avenue.”

Despite critics’ complaints that Hobbs has a Messianic complex that compels him to recklessly take credit for Deep Ellum’s creation, 1984 and 1985 were, in fact, the two years that the area was born as a destination place for Dallasites — albeit not the young professionals who are its current economic lifeblood. Hobbs and booker Jeff Liles brought in then-scary bands such as Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction, 10,000 Maniacs, Wall of Voodoo, and Henry Rollins’ outfit. R.E.M., after a show at the Bronco Bowl, took some acid and headed over to jam after-hours with local musicians until 3 a.m. The New Bohemians, End Over End, and The Trees made a good shot at forging “a Dallas sound.” There was very little neon on Commerce, Main, and Elm back then. It was dark and uncertain like “a frontier,” and because one other live venue — The Twilight Room — played hardcore punk and Goth bands, Deep Ellum began to attract a reputation as a dangerous place by the late ’80s. For a couple of years, the word “skinhead” was synonymous with the neighborhood. “They were like the wolves who came over to devour the lambs and the deer,” says Hobbs. “Everything was black, black, black, whereas at Theatre Gallery it was light. We booked some hardcore bands, and that audience of fascist teenagers began to mix in. I saw 20 skinheads marching down the street in a group, waving a Nazi flag. They’d wait till people got out of their cars, and attack them.”

They were the most unsavory element of an invasion on Hobbs’ “arts party” that, 15 years later, would be filled with more conservative and affluent Dallasites. While stumbling through drugs, alcohol, and increasing commercial demands on his Deep Ellum club, Russell Hobbs went to a tiny revival in the apartment of Theatre Gallery’s janitor in late 1987. You are contributing to the destruction of young lives, the saints thundered, and Hobbs, ever the searching idealist, agreed. He became a born-again Christian and refused to operate an establishment that sold alcohol.

Hobbs walked around, talking about how cool Jesus was, poured out all the Prophet Bar booze, and started serving Biblical menu items such as fish and lamb. Mainstream Dallasites didn’t want to hear about salvation, he says, and the Christians didn’t want to come to Deep Ellum. Theatre Gallery closed in ’88, Prophet Bar (after it had become a downtown mission for eccentric humanity, attracting homeless men and runaway skinheads, and anyone who needed food and a place to sleep) in ’91. What is now The Door operated as a home for the Undermain and New Theatre Company for a few years, and Hobbs stepped in when they could no longer afford to maintain the lease. He is adamant about his all-ages club’s being a place where “kids who are between the McDonald’s age and the drinking age can go and be safe, where alcohol isn’t a concern.

He also insists, despite numerous complaints about the developers’ “theme park” that is the current Deep Ellum, “It’s still the best thing in Dallas. You can go there, eat decent food, and hear a Dallas band. What we had was a fragile thing that couldn’t last. The artists, the dreamers, are the pioneers, and then the businessmen come with the promotional stuff. That’s not cynical; it’s realistic.”