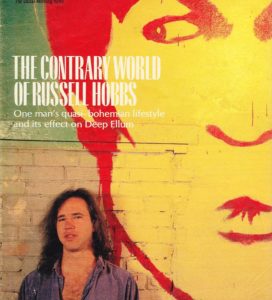

THE CONTRARY WORLD OF RUSSELL HOBBS

By Dusty Rhodes

Published 01-18-1987

When Russell David Hobbs moved into a Deep Ellum warehouse in August 1984, he was looking for a place where he could paint and build things as well as a place where he could park his cars — his Cadillac, his BMW and his Mercedes Benz. Hobbs was 25 at the time. He had been renting a house on the edge of Highland Park, and moved because his neighbors complained when he played the stereo — loudly — at 2 in the morning.

The tenants before Hobbs at 2808 Commerce St. were a coffee distributor and a bail bondsman; before them, a garment manufacturer. The front part of the building had been office space. Soon, Hobbs made it an art gallery and then transformed the cavernous inner-warehouse into a performance hall for avant-garde theater and beginning bands no established club owner would hire. He called this place Theatre Gallery.

The neon above the door simply says TG, but for more than two years that sign has beckoned crowds of clubgoers to experience the newest — though not necessarily the best — in many forms of art. Hobbs has hosted exhibits by fledgling painters, theater productions by fringe playwrights, and concerts by bands with colorful names like Naked Prey, Meat Puppets, The Unforgiven, Screaming Blue Messiahs and 10,000 Maniacs.

“Dallas had a drastic need for a place for true free expression,’ Hobbs says. “Whoever came here that was really serious about what they were doing and showed some kind of concept that needed to be seen or heard, I’d let them do a show.’

Hobbs’ progressive arts philosophy has proved successful in several ways. Theatre Gallery played a significant role in the revitalization of Deep Ellum (before Hobbs moved in, the area had one nightclub; now there are four within walking distance of TG and rampant rumors that several more will set up business in the neighborhood soon). Bands that cut their teeth on TG’s stage can now find “uptown’ gigs at clubs that two years ago wouldn’t let them in the door. And painters like Bill Haveron and billboard artist Ron English, whose work has been displayed in the club’s gallery, are beginning to receive critical acclaim.

But in one way, Hobbs’ enterprise has failed woefully by traditional Dallas standards: Theatre Gallery brings in miniscule amounts of money. A year after opening TG, Hobbs established a second, slightly less progressive venue, The Prophet Bar & Grill. Hobbs claims the name is not a pun, but Prophet Bar’s dual purposes are boldly stated across the top of its burgers-and-fries menu: “An artistic saloon for the sake of money.’ Prophet Bar now nets enough to help TG stay open, but the two clubs operate on a shoestring — a miserably short, frayed shoestring. Hobbs has financed the two places with a lot of help from his family and friends, a series of small miracles and the occasional liquidation of assets.

So the building he leased more than two years ago now houses paintings, plays and bands, but it no longer houses Hobbs’ three classy cars. As a close friend describes the situation, “Russ walks a lot.’ He could have been a yuppie, but he made a U-turn and became a sort of ’80s hippie, quietly protesting against a materialistic society, politely saying “No thanks’ to the American Dream.

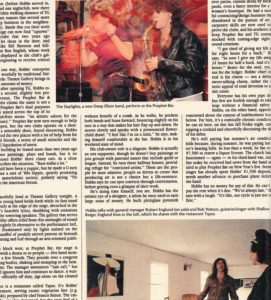

It’s peacefully loud at Theatre Gallery tonight. A sincere young band holds forth while its fans stand reverently at the edge of the stage, drenched in the singer’s heartfelt lyrics, throbbing with emissions from the towering speakers. The gallery that serves as TG’s lobby offers relief from this onslaught of sound and is a brightly lit alternative to the performance hall, which is illuminated only by lights trained on the stage. A handful of punkily attired patrons sit beneath an oil painting and leaf through an arts-oriented publication.

Half a block west, at Prophet Bar, the stage is crowded with a dozen or so people — five band members plus a few friends. They preside over a congress of boogying bodies, shaking and stomping to the beat. No one sits. The manager announces “Last call,’ but the crowd ignores him and continues to dance. A waitress, now officially off duty, jigs alone on the cleared bar.

Upstairs is a restaurant called Tapaz. It’s Hobbs’ newest venture, serving exotic vegetarian fare (e.g. carrot sushi) prepared by chef Francis Simun. The candle-lit cafe, sparsley decorated, has the cozy feel of a starving artist’s living quarters. Widely spaced tables allow privacy, and low windows ringing the room provide a view of the milling nightlife on the street below. If one could ignore the vibrating floor, trembling in time with the band downstairs, Tapaz would be a rather romantic place.

The owner walks in. Hobbs, 28, has long brown hair, vaguely parted on the side and styled seemingly without benefit of a comb. As he walks, he pockets both hands and leans forward, bouncing slightly on his toes in a way that makes his hair flap up and down. He moves slowly and speaks with a pronounced flower-child drawl. “I feel like I’m on a train,’ he says, making himself comfortable at the bar. Hobbs is in his weekend state of mind.

His club-owner role is a disguise. Hobbs is actually an arts supporter, though he doesn’t buy paintings or join groups with patronal names that include guild or league. Instead, he runs these halfway houses, providing refuge for “convicted artists.’ These are the people he most admires: people so driven to create that producing art is not a choice but a life-sentence. Hobbs says he can spot convicts through conversation, before getting even a glimpse of their work.

He’s doing time himself, you see. Hobbs has the artistic eye of a designer, a talent he once used to earn large sums of money. He built plexiglass pyramids over patios, custom decks by backyard pools, even a fancy interior for a chic women’s boutique. He had a successful contracting/design business that he abandoned in the pursuit of art. His carpentry skills are now used to improve the clubs, and his aesthetic skills keep Prophet Bar and TG constantly stocked with cutting-edge sight and sound creations.

“I got tired of giving my life away for eight hours for a buck,’ Hobbs says. “So now I give my life away for 24 hours for half a buck. And it’s a lot better.’ Better for the soul, yes, but not for the ledger. Hobbs’ chief collateral is his charm — not a debonair, sweet-talking charm, rather the magnetic appeal of total devotion to a cosmic cause.

Everyone has his own pipe dream, but few are foolish enough to take the leap without a financial safety net. Hobbs, on the other hand, appears unconcerned about the canyon of indebtedness looming below. For him, it’s a comically chronic condition. So he can sit here, on this late fall Friday night, casually sipping a cocktail and cheerfully discussing the depths of his debts.

He’s still paying last summer’s air conditioning bills because, during summer, he was paying last winter’s heating bills. In less than a week, he has to have $7,500 to renew a liquor license. The clutch has malfunctioned — again — in his third-hand van, and earlier today he received bad news from the band scheduled to play Prophet Bar on New Year’s Eve. Seems the singer has already spent Hobbs’ $1,500 deposit, and needs another advance to purchase plane tickets for the band.

Hobbs has no money for any of this. He can’t even pay the rent when it’s due. “We’re always late,’ Hobbs says with a laugh. “It’s like, our cycle is just not on the first.’

This lax attitude has caused Hobbs constant trouble. Unable to afford a liquor license when he opened Theatre Gallery, Hobbs skirted the law by charging $5 or $6 at the door and giving away draft beer inside. On July 12, 1985, the Dallas Police Department’s vice squad raided TG, arresting the door manager and booking agent and charging them with bootlegging. Hobbs was in Fort Worth that night.

There have been other problems. Some of Hobbs’ former employees say paychecks were sometimes several weeks late; some say Hobbs still owes them money. Bands aren’t always paid what they’re promised; sometimes, in fact, they’re not paid at all. “It’s a real weird situation,’ says Jeff Liles, former booking agent for both of Hobbs’ clubs. “I mean, no band ever did not get paid because Russ was being greedy and just wanted to take a big pile of money and go to the Bahamas or something. The reason why was because the money just was not there.’

In spite of these shortcomings, Hobbs has his fans, people who speak in fawning terms. “Russ was completely and totally responsible for our band,’ says Bob Watson of Shallow Reign. “No one else would give us a chance, because when we met Russ, we didn’t even have a demo tape.’ Shallow Reign now tours both coasts and has released an LP that’s attracting attention from major labels.

“I really do owe a whole lot to Russ, because there’s probably no other place that would have given me an outlet,’ says Jim Heath, a.k.a. The Rev. Horton Heat, leader of a popular rockabilly band of the same name. Having spent 11 years in a series of rock groups, Heath was accustomed to playing “cover tunes’ (note-for-note copies of radio hits), but longed for a place he could perform his repertoire of original songs. Hobbs put Heath on stage at Prophet Bar, and now Heath is in demand all over town. “I guess I can’t be for sure what would have happened if, but I’m pretty sure things would have been a lot bleaker for me and a whole lot of other bands if it hadn’t been for Russ,’ Heath says.

Some of the groups show their appreciation by occasionally performing without charge. “I really think that Russell has done a great thing, and I want to see him keep going,’ Heath says. “That’s really why I sometimes play for free there.’

But Heath and members of other Deep Ellum bands say this charitable attitude doesn’t extend to owners of more traditional clubs. “I don’t really consider Russell a club owner,’ Heath says. “I consider him a guy with an art project that has to have a liquor license.’

Heath is right. Hobbs’ artistic temperament frequently overwhelms his business sense, and Hobbs has been known to make the kind of decisions that are patently pernicious for an entrepreneur. One example, out of many: an ad Hobbs placed in the Dallas Observer last October. Ostensibly intended as a help-wanted announcement, the ad featured photos of waitress Crystal McArthur, bartender Tom Stanco and booking agent Liles. Above the photos were the words: “We take nobodies and turn’em into pros.’

Hobbs now admits the ad was inspired by petty political jealousy. Liles had been lionized by the patrons and press as the creative genius behind the clubs’ record of consistently presenting the best in new music, and Hobbs says he wanted to remind everyone that he was the one who gave Liles that first chance to prove himself as a booker. “It was just impulsive,’ says Hobbs. “I wouldn’t take it back. It was creative advertising.’ The three employees pictured in the ad immediately found better-paying jobs elsewhere (Liles is currently the booking agent for the New Longhorn Ballroom and Club Dada, another Deep Ellum nightspot).

Their anger has subsided now, however, and all three speak of Hobbs as a man with a dream they believe in. “Russ is still the innovator in performance art,’ says Stanco. “The best year of my life was last year, working at Prophet Bar. I miss it.’ On the verge of launching, by request, into the telling of his life story, Hobbs picks up a tape recorder. “Is this on?’ It is. “OK, I guess I’ll tell you the real story then.’

Born in Lubbock “in the same hospital as Buddy Holly!’ Hobbs is the son of Charles and Rosalyn Hobbs, who separated when their son was 10. Charles Hobbs is an architect, now vice president in charge of store planning for Dillard’s Department Stores. Russell grew up in North Dallas, building tree houses and go-carts and excelling in his studies. “I made straight A’s until sixth grade,’ he says. “Then, I started thinking about everything too much.’

As a teen-ager, he played soccer, raced motocross and ran from adoring throngs of girls. “In seventh and eighth and ninth grade, girls liked me. They wrote me notes all the time, but I was scared of girls,’ Hobbs says. “Like at a school dance, I’d see people start kissing . . . and I’d just get out of there!’

He says he loved school because he loved learning. “I was probably the kind of student that didn’t seem like I was really wanting to learn that bad, but I was always like, after class, talking to the teacher about something they inspired me to think about during the lecture,’ Hobbs says. “Then I’d get a C on the test.’

After graduation from Berkner High School (where his classmates voted Hobbs “Best Dressed’), his grandparents encouraged Hobbs to attend the Air Force Academy. “It seemed real fun and everything,’ he says, “but I’m not into rigidity, you know. I’m into like free flow.’ His mother offered to send Hobbs to school anywhere in the world. He chose Richland Community College. Hobbs went there one semester, then transferred to North Texas State, where he studied interior design, business and biology. Meanwhile, he started a successful contracting business.

“He was good!’ says his father. “He was designing things when he was 18 years old. He did a lot of contracting around town. Did real good.’ Once, while the elder Hobbs was unemployed, his son found work with Gordon Sibeck and Associates, an architectural firm. “He called me and said, “Hey, they can use somebody here.’ So I went out and worked there with him, you know. I was a registered architect and here I was working with Russ. He was about 19 or 20 years old,’ Charles Hobbs says.

In the early 1980s, the younger Hobbs got a job converting 150 North Dallas apartments to condominiums. At the same time, he enrolled in a small-business course at Brookhaven Community College. Short of funds needed to meet payroll one week, Hobbs borrowed $30,000 through his teacher, who was the executive vice president of a bank. “I used to tell people I’m a contractor and an artist, so I’m a con artist,’ Hobbs says, with a grin. He repaid the loan in full.

But playing the role of “big businessman’ felt uncomfortable to Hobbs. He was wearing suits and driving a new truck, spending nights drinking champagne at Nostromo, painting and drawing in his spare hours — all this at the age of 23. “It was at a time in my life when I had like a lot of business and work and employees and money and taxes and all that, and I just had to get out of it,’ he says. On the eve of 1982, Hobbs decided it was time for a change. He spent the next year at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, where he studied business and art.

“I needed like an accelerated growth period in my life,’ Hobbs says. “I ripened in Alaska, you know? Everything came together and I knew what I wanted out of life. I wanted to work with people, creative expression, spiritualism.’

He returned to Texas in 1983 and his long-time friend, Logan Daffron, got Hobbs a job at the Greco-Roman Festival. Daffron, a photographer, had documented Hobbs’ design projects for his contracting portfolio. But by the time Hobbs returned from Alaska, Daffron had changed vocations. He was a juggler. At the festival, he got Hobbs an equally bohemian job that involved dressing as Jason of the Argonauts.

“All the other actors at the festival would always come up to me and go, “What do you do? ‘ I’d say, “What do you mean? I’m doing it!’ ‘ Hobbs says. His job, as described by the festival owner, was to “vamp women.’

“He would go to the very front gate and get these old ladies and lead them through to the very back of the park, get ’em someentertainment, dump ’em off and go back and vamp some more women,’ says Daffron.

When the festival closed, Hobbs took a job designing and building E’Lanes, a now-defunct Lovers Lane boutique. The fee he earned on this project enabled Hobbs to lease the building that is now TG. He moved into the warehouse intending to host parties now and then, but he had no premeditated plans to establish a nightclub. Soon, though, he met a group of North Texas State artstudents searching for a gallery in which to present a show. Hobbs offered his space.

The artistic grapevine spread the word: This crazy dude in Deep Ellum will let almost anyone put on a show. Playwrights, painters and musicians began knocking on Hobbs’ warehouse door. He welcomed all comers, and Theatre Gallery was born.

It’s not the kind of place you would take your mother. Theatre Gallery is infamous for its steep, dangerous stairs, its cave-like darkness, its earsplitting bands, its junkyard decor and its wretched toilet facilities. Its centerpiece, the stage, is built with wood from a stage on which a punk band called The Dead Kennedys once stood. It is a stage originally used during the GOP convention for a protest concert billed as Rock Against Reagan.

Here, teens in the grips of rebellious urges can dress as funky as they please. Here, they can be aurally assaulted by live music played by bands with fresh memories of adolescent despair. And here, they can sit on the gallery floor and just talk. Above all, they can revel in the anti-establishment atmosphere, the feeling of being on the fringe. In fact, Hobbs admits that the warehouse’s small upper lofts sometimes provide temporary shelter for runaways, who are assigned janitorial chores in lieu of rent.

TG is open to all ages, but as one patron says, “It’s a very kid-oriented place.’ Prophet Bar represents Hobbs’ answer to needs not met at TG. The clubs function “like ying and yang,’ he says.

“(Prophet Bar is) a place that I could have what we couldn’t have over here at TG,’ Hobbs says. “Which is — older people. Coffee. Chairs.’

Prophet Bar consists of two like-size rectangular rooms, connected by a broad doorway. The west room features a stage overlooking a cement dance space surrounded by tables and chairs from a club once owned by Jack Ruby. The east room has a bar along one wall; black naugahyde booths with wobbly tables fill the remainder of the space. The walls of both rooms are completely covered with fantastic murals.

The two clubs lack the kind of glamorous frills Dallas’ night animals have come to expect — fake fog, laser lights, video screens, leggy waitresses in fashionable garb, snobby door managers, exotic drinks, matchbooks printed with the club’s logo. But what TG and Prophet Bar lack in glitz, they make up for with guts. They offer art in lieu of amenities. Hobbs attributes the success –such as it is — of the two clubs to the synergy created by combining music, theater, painting and sculpture in one place.

“I don’t know what came first,’ he says. “Dallas crying out for a place to have this art scene grow? Or was I this genius guy, am I from ancient Greece, sent here to cultivate the arts in Dallas? I don’t give myself that much credit. I think nature took its course. I was just the guy that said, “Why not?”

And he didn’t wait for the answers. At least not the pragmatic, obvious ones. Half-cocked, impulsively and with funds to cover only about two months’ rent, he plunged headfirst into nightlife entrepreneurship, one of Dallas’ riskiest businesses. He describes his endeavor in the noblest of terms:

“I’m not in it for the business side of it. I’m in it for the dream side of it. And that is what we can all become. “Theatre Gallery is a force that’s for people. Theatre Gallery is very good for mankind. It offers a void of bureaucracy. It offers just straight-on hope and a chance for people that are unproven. Like it made me more than I was; it has made bands, painters and theater people into more than they were. It’s just something the world needs.’

Is this mere rhetoric? Or is it Hobbs’ sincerest belief? Whatever, it would seem he doesn’t have to be here, living in TG in a tiny, fluorescent green loft with one rocking chair, one abused recliner, one lumpy-looking mattress and piles of papers on a dirty floor.

“Oh listen,’ says his dad, “I told him he could come over here (to Little Rock, where Dillard’s is based) and I’d start him a contracting business and guarantee him that he had good jobs. I could get him anything he wants. I could set him up in business, supply him with the work in Arkansas or in Dallas. There’s nothing to that . . . .He could be a successful businessman if he wanted to sit behind a desk and do all that kind of stuff, run a job, run around on airplanes. He could do it. No doubt about it.’

Shannon Wynne, co-owner of Lower Greenville’s Fast and Cool club, also believes Hobbs has a future waiting in the contracting field. Hobbs worked for Wynne as general contractor for Fast and Cool. “Oh, he did a half-assed job. But he finished it. He did what he said he was going to do . . . . I think he’s probably matured quite a bit since then,’ says Wynne. “I like Russell, though. He’s got a good head. He’s a total f— up, but he’s got a good head. He’s got a good heart and he’s got a real creative spirit about him.’ Wynne is planning to open a new club, and he has already asked Hobbs to consider taking the contracting job. Hobbs says he may accept, if the price is right, but he shows no signs of returning to the business full-time. He seems to becarefully avoiding the smoothly paved path that would easily lead him to dreaded yuppiedom. Hobbs prefers to explore the untamed underbrush of art, and so far he has refused offers from potential investors who could clear the way. His only official business partner is Logan Daffron, the juggler.

“TG is never going to be a big money-making enterprise because of its philosophy,’ Hobbs says. “But see, this is a total experimental, you know, low-capital, high-dream project.’

In December, when his bank account was at an all-time low and his debts were reaching an all-time high, Hobbs, apparently seized by the Christmas spirit, devoted his energies to staging a benefit concert that raised several hundred dollars for the Dallas Family Shelter. Such unorthodox business decisions manifest Hobbs’ motto on coping with the dearth of funds: “Don’t worry. It’llhappen.’ Always, in the 11th hour, Hobbs comes up with the needed money.

In the beginning, he would simply sell a car. The Cadillac went first, sold to Robert Lee Kolb, leader of the band Local Heroes. Later, when several bills came due, Hobbs borrowed $5,000 from Daffron’s dad, a land developer, who wanted the title on the Mercedes as collateral. But Hobbs continued to borrow instead of repay, and Daffron’s father eventually claimed the car. The BMW, on the other hand, was not actually sold. Driving it one day, Hobbs was hit by a well-insured motorist. About that time, Hobbs was trying to help the band Three On A Hill put their music on vinyl. The check from the insurance company was used to finance the band’s first record.

Other times, Hobbs cajoles friends into lending or giving him money. And sometimes, Hobbs resorts to calling his father. A reluctant supporter, Charles Hobbs has given his son $50,000 in CDs to be kept in the bank and borrowed against, even though he wishes his son would give up this crazy dream and return to contracting. “I’d rather for him to do something like that than what he’s doing, but you do your own thing,’ the father says. “He’s the only boy I’ve got. If I have to help him, I have to.’

Then occasionally, some miracle occurs, like the time Hobbs was in desperate need of $2,800 to buy a liquor license bond. “So I’m sitting there pulling my hair out,’ he says, “going, “Where are we going to get the money for this?’ All the sudden, these frat guys come walking in, and they go, “We want to have a party here next week.’ ‘ Hobbs rented them the Prophet Bar for $2,800.

“My great-grandfather escaped from Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution,’ Hobbs says, “came to Alabama and he was a drummer in the true sense of the word. He was walking around with a cart, “Apples! Oranges! Peaches!’ Whatever. So I’m a drummer, you know, with my mouth. That’s my instrument.’

So far, Hobbs has played it like a true virtuoso; his clubs have survived longer than anyone expected. But this achievement has taken more than mouth; it has required sacrifice. The constant money worries must be a strain, and Hobbs’ living quarters are not much better than a sleeping bag in a tent. But Hobbs looks at the whole situation and says he feels lucky.

“I’ve got a project to be involved with. I’ve got a thing going. There’s lots of people out there that don’t have a thing going. TG is something to work on. It’s an infinite project. The bathrooms themselves could take up a whole two months. If we ever get around to it,’ he says with a laugh. “But if you’ve got something to dream for, then you’ve got something to live for. And you’re going to be happier.’ Dusty Rhodes is a regular contributor to Dallas Life Magazine.

know a little more about you.